Search Preference Menus: No Auctions Please

This is the third in a series of posts about search preference menus.

As Google’s search preference menu for Android devices in the European Union goes live, the process to be a part of this preference menu is based on a recurring auction model, offering Google-alternative search engines the chance to bid for three spots in each EU country, with the proceeds going to Google. We won a spot in the first auction, and we’re glad Android users in Europe will finally have the opportunity to easily pick DuckDuckGo as their default search engine.

However, given the current construct, it’s very unlikely we will remain an option in next year's auctions. That's because search engines who squeeze money out of every last drop of people's personal information (including ISPs and arbitrage players that will participate in next year's auctions) are easily able to outbid search engines like us that respect people's privacy. This auction remedy, proposed by Google, was constructed to make Google money, not to provide meaningful consumer choice.

That’s why we strongly believe it is in the best interest of consumers to throw out this auction model and replace it with a non-pay-to-play model that includes more than three alternative choices.

Quite simply, a preference menu that is missing the search engines consumers expect, and that is instead filled with search engines that don't deliver good consumer experiences, is a sham. Our research shows that, after Google, people would choose DuckDuckGo second most, and more generally want to be able to choose a private search engine.

In particular, an auction model disadvantages search engines that:

- Put user experience over monetization and so show fewer ads.

- Put privacy before profit and so make less money per ad shown.

- Give away a substantial portion of their profits to good causes.

DuckDuckGo does all three of these things. Also, DuckDuckGo and most other search engines syndicate search ads from larger companies, splitting revenue with them. These larger companies are therefore by definition further advantaged in any auction process relative to their syndication partners: they do not have revenue splits and they know what their syndication partners can reasonably bid.

In short, the pay-to-play auction model is rigged in favor of big companies and search engines with intentionally ad-heavy search results. They can afford to pay many times more relative to smaller providers like us, even though we have a high numbers of users because of our consumer-friendly search experience. Unless this auction format is fundamentally altered, consumers will eventually be forced to pick from options who can pay the most, not from the options that they actually want.

The Solution: Throw Out the Auction

An easy solution exists: throw out the auction. It simply isn’t necessary, as history has already shown. A search preference menu recently shifted Android market share in Russia without an auction.

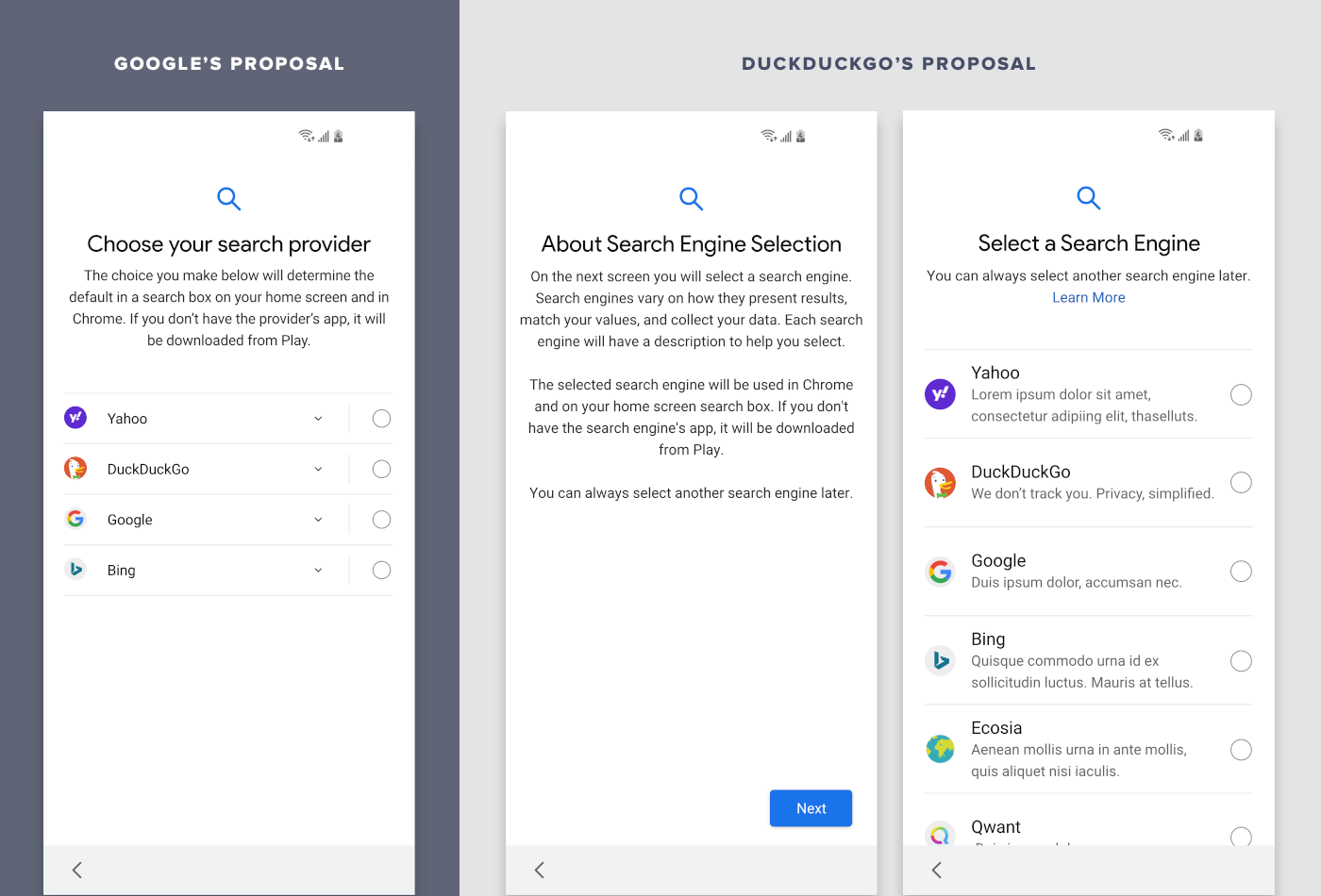

Additionally, in 2010 Microsoft created a successful browser preference menu without an auction. In that case (depicted below), the top five browsers by market share appeared first in random order, followed by a second, randomly ordered tier. And importantly, no browsers paid for placement!

This two-tier system solves the problem of making sure the search engines that consumers most expect appear first, while still allowing for other search engines to be included in the menu. Our previous post explains in detail how this could be visually designed.

When we presented people with a longer list of search engines, those people selected more non-Google search engines. In other words, more choice means a more diverse search engine market, assuming the choices people expect to to be there are there.

Winning and Losing Auctions

For this first year of Google's EU preference menu, three auctions are being held. The number of bidders in these initial auctions is limited because Google first designed the process as a “first price” auction (meaning you pay what you bid), imposed a variety of other eligibility requirements (e.g., in-app language localization across all EU countries), and set a tight deadline to submit applications. We suspect this resulted in most search engines either not knowing about the deadline in time to meet the eligibility requirements or finding the original format to be completely unacceptable, and so they didn’t submit the necessary paperwork on time.

When, later, Google revised the process to a “fourth price” auction (meaning everyone pays the first losing bid after the three winning bids) and also revised the eligibility requirements (e.g., English localization is now accepted everywhere), Google did not re-open the 2020 auctions to companies that didn’t earlier apply. But in 2021, Google is planning to start over, allowing all general search engines to bid, including sites you don't normally think of as search engines like ISPs and arbitrage sites (that buy keywords and send you to pages of ads instead of actual search results).

Thus, starting in 2021, we expect many more bidders, most all of which can make more money per search than us because of their less consumer-friendly business models. In other words, it is very likely we will be easily outbid and not be on the preference menu in next year's auctions and thereafter.

We also expect new search engines to be created for the express purpose of taking advantage of this preference menu format. It is relatively easy for a new or existing company to create a sub-par search engine with a very high behavioral ad load and poor search results (e.g., lacking useful instant answers like maps and facts). Hundreds of these sites already exist, such as ISP start pages.

You would think that if people selected one of these sub-par search engines, they might quickly switch to another after getting poor search results, but currently the preference menu is designed in a way that it is only accessible when setting up a device. That is, it is impractical to get back to the menu (it's only possible by resetting the device) and so it isn't easy to change your selection.

Debunking Reasons for the Auction Model

It’s our understanding that the auction model has been adopted because it supposedly (a) provides money for Android development and (b) determines who most deserves to be listed in an efficient, market-driven manner.

First, Google does not need money from other search engines to fund Android development. That’s just silly. Google is sitting on over 100 billion dollars in cash, which is growing by the day.

Second, we already have an efficient, market-driven mechanism to determine who most deserves to be there: market share, as used in the Microsoft example above. Another way, not dependent on any third parties, would be to order the list dynamically based on how often a search engine is selected in a given market.

In any case, if organized by market share or dynamically, we believe Google still shouldn't be listed first, and that there should be more than three alternative choices given. This design results in the best consumer experience and the most search engine market competition. As it stands now, by only having three alternatives, Google has manipulated the preference menu to introduce false scarcity. This scarcity is designed to result in over-subscription to the auction, further inflating the cost to competitors of participating (and thus the financial benefit to Google of them doing so).

Moreover, as mentioned above, because so many search engines syndicate from larger upstream providers, an auction model is intrinsically biased. The larger upstream providers will always know what their downstream partners earn and can always outbid them.

Unless the auction model is thrown out, we believe DuckDuckGo and many other search engines that consumers actually want to use will not be on the search preference menu in the long term. At the same time, and as explained in the first post of this series, we still believe a search preference menu can deliver meaningful search engine choice to consumers and significantly increase competition in the search market.

In other words, if you want to incentivize greater consumer choice in the search engine market, a properly designed and structured preference menu is a great way. But an auction format is not the proper structure, and arguably the worst possible way to implement it.

For more privacy advice follow us on Twitter, and stay protected and informed with our privacy newsletters.